Homicide detectives in Arlington work on cold cases in their down time.

They evaluate evidence again, revisit witnesses who may remember new details and use DNA and technology to help close these investigations, some decades old.

Now, they’ll have some help.

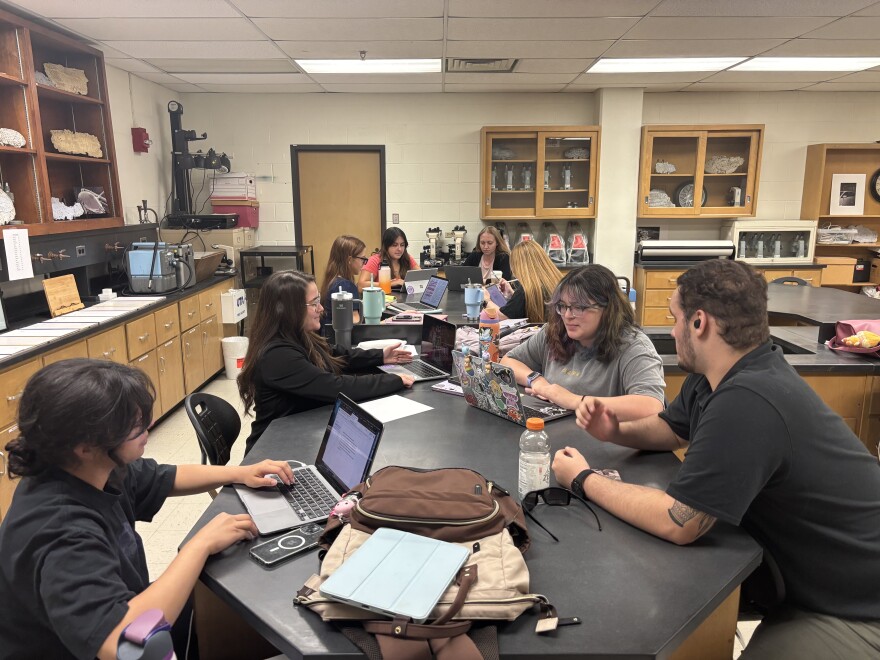

Twice a week, 15 students at UT Arlington — most of them criminal justice majors — meet in a windowless room in the life sciences building. Broken into three groups, the students pour over old police reports, review witness statements, examine crime scene images and form their own questions, recommendations and, depending on what they find, maybe even new theories.

“These students are studying everyday modern techniques, modern sciences, modern ways to work cases,” Assistant Police Chief Kyle Dishko told KERA. “They don't have any predisposition of the way we've always done it.”

The class has been given every report, photograph and statement generated in their cases. Although students don’t get to see the actual physical evidence in class, they can recommend retesting something for DNA or look at the evidence from a different angle.

The details of the cases the students are examining aren’t public. Dishko and Professor Pat Eddings, who teaches the advanced course on cold case investigation of students working these cases, said that’s to keep the investigation secure and keep families and friends of cold case victims from trying to guess which cases the students are looking at in their class.

All Dishko said he could share was that the cases are decades old.

Examining the evidence

The collaboration can create opportunities to break a cold case at the same time that it presents challenges. Newer technology allows for DNA testing that wasn’t possible when the crime happened. And while some witnesses may have died between now and then, others could remember or feel comfortable sharing details they didn’t the first time around.

There are also things original detectives may have missed or not thought about. That’s what Jacey Concanno’s group is looking at in class.

Concanno, who wants to work as a crime scene investigator after she graduates, and four other students have spent months looking over the mountain of police writeups, interviews, notes and reports to familiarize themselves with the case they’ve been assigned.

“We're obviously looking for any kind of physical evidence, so any kind DNA evidence we're going to keep our eyes open for,” she said.

But other evidence can be helpful, too. Some details can be found by looking at old crime scene photos, like what footwear a suspect may have worn or alternative theories about how and why someone was killed, Concanno said.

Things like that could open new doors and spark innovation in the group of student detectives – something Dishko said is a big goal.

Most cold cases in Arlington are investigated by detectives who don’t have a hot case on their desk at the moment. Others are reviewed by retired detectives who want to revisit old unsolved cases they worked or help find answers in others.

Dishko said the experience and insight from retired detectives can be a game changer, but so can fresh ideas and mindsets brought by students who haven’t actually worked cases like these.

It’s something Eddings said inspired her to pitch the class to police and the university. She had an Arlington police sergeant visit one of her classes last year and said he mentioned on several occasions that one of the biggest problems investigating cold cases is a lack of time.

Eddings, who is the Director of the Forensic Applications of Science and Technology minor program as well as a senior lecturer in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, said she realized she might be able to help with that.

“I've got these brilliant young minds that would just be more than happy to take these cases and dissect them piece by piece by piece and put the facts back together and maybe a different viewpoint of what had been seen years ago,” Eddings said.

Police-UTA collaboration takes shape

The university and police department decided to move forward with the idea and began accepting applications for the class in the summer. Eddings said there were around 20 or 25 applicants who were narrowed down to the 15 who sit in the classroom every Tuesday and Thursday.

That’s why most of the class shows up hours before its official start and will hang around for hours after. Eddings said the students are so committed to investigating their cases so she can be in the classroom for those students like criminal justice senior Joie White.

White and the group she’s in are trying to find outside-the-box approaches to the cases.

“We're trying to look at it is like, ‘don't think it's the obvious.’ ” White said. “You might read all the documents or just read a summary of it and you might think it is one thing. But we're trying to focus on not assuming it's a classic person and to look at further details.”

She said her group is looking at those documents and photos for evidence that aligns with the possibilities detectives have put forward since the investigation started, but at the same time they want to consider suspects that may not fit any sort of traditional mold.

Preconceived ideas about a case won’t help close it, White said. That’s why the group she’s in is working to be mindful not only of their own biases, but the biases that might have impacted the original investigation.

“There might be a lot of biases already, like within certain cases, and in a lot other cases,” she told KERA during one class last week. “We're pretty much trying to look at all the options instead of just being biased on one suspect or one person.”

Carina Rios is part of the third group. She’s studying criminology with a minor in forensics and is currently in the middle of an investigation with another department’s crime scene investigation unit.

Her focus is reflected in that.

The things she’s learned in class paired with her real-world experience through the internship have helped her approach on the evidence her group is looking at, and her experience in the class has helped her in the internship, too.

“What could help us, you know, further this investigation that we're looking at by just by going through physical evidence?” Rios said she asked herself at the beginning of the semester. “I've gotten so much help from my internship to learn what advancements have been made.”

Those include advancements in forensic genealogy, a method of identifying suspects by looking for genetic relatives. The DNA found at a crime scene can be compared to those taken from other people who had run-ins with law enforcement or who submitted samples to companies like Ancestry DNA or 23andMe.

Forensic genealogy was used in finding Joseph James DeAngelo, better known as the Golden State Killer. Arlington police used it to identify Bernard Sharp, the man they said killed Terri McAdams. DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 murders and 13 kidnappings in 2020 and was sentenced to life in prison. Sharp killed himself months after he murdered McAdams.

For Rios, a major focus in her group’s cold case is identifying collected DNA (or evidence that could have some usable DNA) to open up new leads.

Eddings said the groups are made up of students from diverse backgrounds, which helps in exploring different approaches to investigating the crimes. Bringing those students and their ideas together is one of the strengths of the class.

The students, who are working with Arlington homicide detectives as they work the cases, will present an update in October. At the end of the semester, each group will submit a report with their findings and suggestions for the detectives who are working their cold cases.

Got a tip? Email James Hartley at jhartley@kera.org or follow James on X @ByJamesHartley. Email Andy Lusk at alusk@kera.org.

KERA News is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.