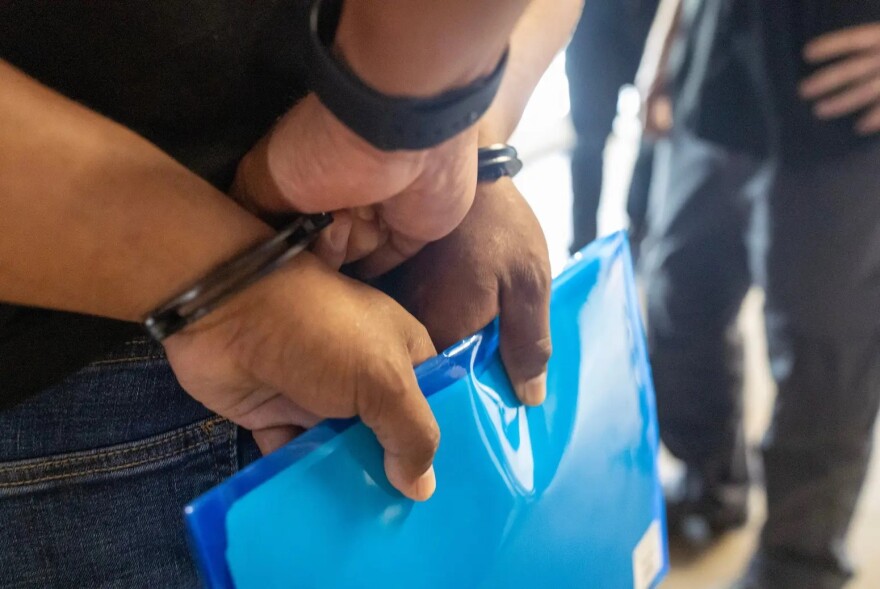

President Donald Trump recently made two big steps toward fulfilling his promise to carry out the largest deportation program in American history — changes some worry are denying due process to detained migrants.

Earlier this month, the Trump Administration ended bond hearings for undocumented people in detention, eliminating the opportunity for them to have a judge “look at whether the detention was actually appropriate,” said Denise Gilman, a law professor who directs the Immigration Clinic at the University of Texas at Austin.

The administration also fired 20 immigration judges across the country earlier this month, bringing the total of judges who have either resigned or been fired since January to 106 — out of roughly 700 judges serving nationally.

This "one-two punch” of having fewer judges moving cases forward and migrants now unable to access bond hearings is positioning Texas — home to most of the detention beds in the country — to face an extreme backlog of immigration cases, said Heidi Altman, vice president of policy at the National Immigration Law Center.

Without bond hearings, all detained migrants now have to stay in detention centers for the duration of their removal proceedings, which can take months — and in some cases, years. On top of that, wait times may expand since there are fewer judges hearing cases.

“ICE becomes the jailer and the judge,” Gilman said. ”They decide who stays in detention and then there is no review of that detention.”

Federal detention facilities are already overcrowded and understaffed because of a bottleneck of more than 4 million pending cases, according to the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

The firing of immigration judges has been slowly happening behind the scenes since Trump returned to the White House.

Among those who have been fired, many were based in Texas cities, including Houston, El Paso and Laredo, according to the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers, the union representing immigration judges. But it’s unclear how many terminated judges worked in Texas.

Trump said on Truth Social in April that eliminating migrants’ ability to challenge their detention in court is necessary to fulfill his deportation promises.

“We cannot give everyone a trial, because to do so would take, without exaggeration, 200 years,” he wrote. “We would need hundreds of thousands of trials for the hundreds of thousands of Illegals we are sending out of the Country. Such a thing is not possible to do.”

Immigrant-rights activists, however, are concerned that the loss of immigration judges and bail hearings for migrants means the loss of basic constitutional rights for people navigating the country’s immigration system.

Non-citizens, including undocumented immigrants, are entitled to due process rights according to the American Immigration Council. The nonprofit points to the Fifth Amendment, which protects the right to due process to all “persons,” not just citizens.

“We are just chopping away” at due process for migrants, Altman said. “It's like death by 1,000 paper cuts.”

Eliminating bond hearings

Todd M. Lyons, acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, on July 8 sent a memo to officers that migrants should be detained “for the duration of their removal proceedings.”

The sudden change is going to test the capacity of the country’s detention centers, Gilman said, including the 21 facilities in Texas that held more than 12,000 people in June, making it the state with the most ICE detainees in the country. Louisiana trails Texas with just over 7,000 detainees.

“Detention centers are already full, we're at the highest levels of detention that anybody has ever seen,” Gilman said.

But Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin told the Washington Post that ICE will have “plenty of bed space” because Trump’s budget bill passed by Congress earlier this month allocates around $170 billion on border and immigration enforcement.

The administration recently announced plans to spend $1.26 billion to build a 5,000-bed tent camp in Fort Bliss, an Army base in El Paso, which would make it the largest immigration detention center in the country. The government plans to have that facility open by September 2027.

But Gilman said detention centers are already overcrowded, and ending bond will make that crowding worse.

One of the functions of bond hearings is to limit detention to ”cases where it's needed to prevent flight risk or danger while somebody's undergoing their immigration proceedings in immigration court,” Gilman said.

Without them, “migrants who are detained by ICE will no longer have any ability to question their detention — to challenge their detention before an immigration judge,” she added.

Plans to hire more immigration judges

The 103 terminated judges include 54 who were in their two-year probationary period, according to the union. Forty-six others resigned, while three judges were transferred to another department and are no longer hearing cases.

“The judges who were fired were mostly people who were appointed during the Biden administration,” Gilman said. “It's pretty clear that the intent is not just to get rid of immigration judges in a neutral manner, but rather, to get rid of immigration judges that the administration thinks will not be favorable to Trump priorities.”

Immigration judges, Altman said, are in a unique position compared to other federal judges because immigration courts are within the Department of Justice, making judges vulnerable to being fired if their rulings aren't aligned with the president.

“Immigration judges are simply employees of the Department of Justice at the whim of the executive branch, at the whim of their policy measures, at the whim of their threats of firing,” Altman said. “And that makes it very easy for the executive to impose coercive action on them that influences their decision making.”

Having nearly 15% of federal immigration benches empty while the administration is ramping up arrests of undocumented migrants could put pressure on the remaining judges to get through cases faster, Altman said.

“I see more of a risk of bad calls,” she said. “Immigration judges with more cases under time pressures may not have an opportunity to analyze the questions [in a particular case].”

The administration said a portion of funds from the budget bill allocated to immigration enforcement will go toward raising the number of judges to 800 and hiring more staff to support them, but Gilman said that may not be enough.

“Even if they do hire up to 800 immigration judges, there's 4 million cases in the backlog — that's nothing,” she said.

Sirce Owen, acting director of Executive Office for Immigration Review, the federal agency that conducts immigration court proceedings, appellate reviews, and administrative hearings, sent a memo to judges in April pushing judges to take “all appropriate action to immediately resolve cases on their dockets,” because of the current backlog of cases.

“What we see here is the administration doing whatever they can to expedite as many deportations as they can,” Gilman said, “not only without regard to due process for the people going through the system, but also without regard to whether it just breaks the system entirely.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.