Updated Thursday, Nov. 17 at 7:12 a.m.

Texas’ execution of Stephen Barbee Wednesday evening was prolonged while prison officials searched for a vein in the disabled man’s body, according to a prison spokesperson.

Barbee, convicted in the 2005 murders of his pregnant ex-girlfriend and her child, had severe joint deterioration which prohibited him from straightening his arms or laying them flat, according to court records. His attorney had recently tried to halt his execution because he feared the process with Barbee’s disability would result in “torture.”

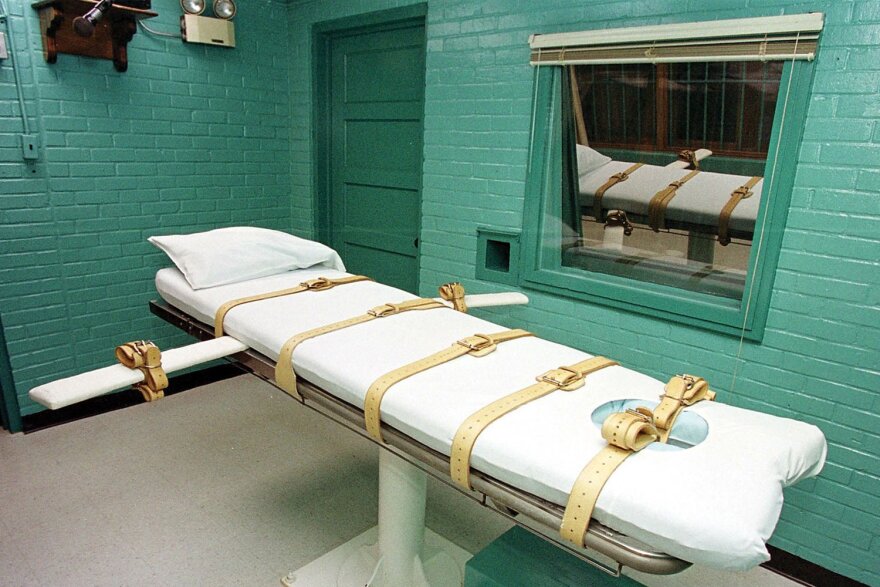

But courts rejected the appeals, noting that prison officials had vowed to make special adjustments to the death chamber’s gurney to accommodate Barbee.

Still, it took much more time to carry out the execution than is typical in Texas. Reporters walked into the prison around 6 p.m., signaling the execution was about to begin. But for an hour and 40 minutes, no one came back out, causing anti-death-penalty protesters outside to grow worried that something had gone wrong. It is uncommon for executions to last more than an hour.

“Due to his inability to extend his arms, it took longer to ensure he had functional IV lines,” prison spokesperson Amanda Hernandez said in an email Wednesday night.

Barbee was pronounced dead at 7:35 p.m., nearly an hour and a half after he was strapped into the death chamber’s gurney, according to the prison’s execution record.

Within minutes of being strapped on the gurney, an IV was inserted into his right hand, at 6:14 p.m., but it took another 35 minutes for an additional line to begin flowing in the left side of his neck. All the while, his friends watched through a glass pane adjacent to the chamber, according to a prison witness list. So did the friends of the murder victims — Lisa Underwood and her 7-year-old son Jayden — as well as Underwood’s mother.

About 15 minutes after the IV was inserted into his neck, he gave his final statement, thanking God, his minister and his loved ones.

“I just want everyone to have peace in their heart, make eternity with Jesus, give him the glory in everything you do. I’m ready,” he said, just before a lethal dose of pentobarbital was injected at 7:09 p.m., 26 minutes before he was pronounced deceased.

Hours before the prisoner’s scheduled death, Barbee’s execution was paused as courts battled once again over the state’s handling of the prisoner’s religious rights in the death chamber.

Federal courts this month went back and forth over Texas’ execution policy and the findings of multiple U.S. Supreme Court rulings largely requiring the state to allow prisoners’ religious advisers to audibly pray and touch them in their final moments. On Tuesday, a district judge essentially halted Barbee’s pending execution, stating Texas’ prison system can only kill the death row prisoner after creating and adopting a new execution policy that clearly lays out his final religious rights. But after the federal appellate court and the U.S. Supreme Court both ruled in favor of the state early Wednesday afternoon, Barbee’s execution was put back on track.

Barbee, 55, was convicted of the 2005 murders in Tarrant County. Under police interrogation, Barbee confessed to the killings, saying he feared Underwood would tell his ex-wife he was likely the father of her unborn child and he would have to pay child support. Soon after, he recanted the confession, which his lawyer argued was “the product of fear and coercion,” and he had since maintained his innocence.

Instead, Barbee said his co-worker Ron Dodd, also a defendant in the murders, committed the murders alone, and he helped Dodd hide the bodies. After Barbee was sentenced to death, Dodd pleaded guilty to tampering with physical evidence and got 10 years in prison, acknowledging he helped Barbee dispose of the victims’ bodies.

Barbee’s first execution date, set for 2019, was stopped by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to further investigate whether it was a violation of Barbee’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel when his trial attorney told the jury he was guilty against his wishes. In a Louisiana case, the U.S. Supreme Court had recently ruled that defendants have a right to insist their lawyers don’t admit guilt even if the attorneys believe such a concession is the best shot at avoiding the death penalty.

Early last year, the Texas court finally handed down a highly technical ruling concluding Barbee wasn’t eligible for a new trial because he didn’t tell his attorneys clearly enough that he wanted to maintain his innocence. The judges said that although Barbee repeatedly told his lawyers that he was innocent and would not plead guilty, and although he was shocked at the concession of guilt at his trial, he didn’t tell them his defensive strategy included an innocence claim, so he wasn’t wronged under court precedent.

After the ruling, Tarrant County officials moved for a new execution date, set for October 2021. That time, it was canceled by U.S. District Judge Kenneth Hoyt of Houston while the U.S. Supreme Court weighed another Texas man’s case in a series of rulings over the Texas prison system’s handling of prisoners’ religious rights in the execution chamber. Barbee had requested that his spiritual adviser pray over him and lay his hand on him as he died, a practice which had recently been barred by prison officials.

This March, the high court ruled that Texas’ execution policy likely violated a prisoner’s religious rights, and prison officials said it would make adjustments to execute people in line with the court’s intent.

Before Wednesday’s execution, his lawyers still argued there was an unacceptable lack of clarity in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s execution policy regarding religious practices. Though the prison officials conceded to following the orders of the nation’s high court, the practice wasn’t put into the state’s execution policy.

Hoyt agreed, saying earlier this month that Texas could carry out Barbee’s execution only if it updated its execution policy in a clear and consistent manner with U.S. Supreme Court rulings.

“TDCJ is now operating under an unwritten policy where prison officials may unilaterally decide whether to allow an inmate’s requested accommodation … the accommodation may be withdrawn at the will or caprice of any prison official at the last moment,” Hoyt wrote in his ruling.

Prison officials swore in court affidavits that Barbee would be allowed to have his adviser touch him and pray as he dies. Federal appellate judges said Friday that Hoyt’s ruling was too broad, extending beyond Barbee’s needs alone, and sent it back to Hoyt to be revised. On Tuesday, Hoyt issued a new ruling mirroring his previous one but applying it to Barbee only.

“Texas [TDCJ] may proceed with the execution of Stephen Barbee only after it publishes a clear policy that has been approved by its governing policy body that (1) protects Stephen Barbee’s religious rights in the execution chamber … and, (2) sets out any exceptions to that policy, further describing with precision what those exceptions are or may be,” Hoyt said in his injunction.

On Wednesday afternoon, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals tossed the injunction, saying Hoyt can’t order the state to devise a new execution policy. Instead, two judges said a proper order would have been to require the prison to follow its word and allow Barbee to have his spiritual adviser present, audibly praying and laying hands on him as he died.

Barbee’s lawyers had also moved to stop his current execution because they said his disabilities would result in extreme pain if he is strapped to a gurney as prisoners typically are in Texas executions.

For 15 years, Barbee had increasingly lost his range of motion in numerous joints, resulting in him being unable to straighten his arms. His disability had long been documented in his prison medical records, resulting in him using a wheelchair and needing a tool to clean himself after using the bathroom, according to court filings. The prison used handcuff extensions on him because he couldn’t put his hands behind his back.

“If someone wants my arms to straighten out in any way, I guess one would have to break my arms, because even forcing them, they won’t straighten,” Barbee said in a written affidavit last year. “It’s been like this for years and it’s getting worse.”

Last week, the prison warden said in an affidavit that Barbee would not be required to straighten his arms on the gurney. Hoyt dismissed the case Tuesday afternoon, saying the prison had told Barbee months ago he would be accommodated.

“The leather straps that secure his arms to the arm rests are adjustable … which allows for his arms to remain bent,” Kelly Strong, the warden of the Huntsville Unit, said in her affidavit.

“Moreover, while the crook of the elbow is the preferred location for the IV insertion during an execution, the IV lines have been inserted in other locations when a suitable vein could not be utilized,” she said.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2022/11/16/texas-execution-stephen-barbee-tarrant-county/.