A study of Dallas County eviction cases found most tenants lose their cases, forcing them out of their homes and leaving a permanent mark on their record that makes it harder to find housing in the future.

The Child Poverty Action Lab observed nearly 1,300 eviction cases over a nearly six-month period, providing a picture of how eviction cases play out that is rarely seen because courts produce little public data.

The nonprofit found renters rarely have legal representation, though they fare significantly better when they have a lawyer. Their landlords are far more likely to have a lawyer. The study also shows evictions are adjudicated at a blistering pace, with judges taking about four minutes, on average, to rule.

KERA requested an interview with the justices of the peace who preside over the three courts that handled most of the observed cases. Judge Adam Swartz, a justice of the peace representing northern and eastern Dallas, the Park Cities, Richardson and Addison, was the only one who responded. The other justices of the peace were Judge Thomas Jones and Judge Sara Martinez.

Swartz called the study “solidly put together and very meticulous,” and said he thought it seemed “fundamentally unfair that if you can afford an attorney, you have a 93% chance of keeping a roof over your head.”

While CPAL doesn’t advocate for specific policies, tenant-rights advocates say the data provides further evidence of a system skewed unfairly in favor of landlords.

“This is America where we believe in the rule of law, and we have hard data that shows the rule of law is a myth [in eviction courts,” said Mark Melton, whose Dallas Eviction Advocacy Center provides free legal help for renters facing eviction in Dallas County.

The study is the second release from an ongoing court observation study, said CPAL’s Director of Housing Initiatives Brianna Harris.

“It started off as a pilot trying to collect, analyze and just understand better how the eviction process unfolds for all parties — for tenants and landlords and property managers — and to just better understand the barriers,” Harris said.

Attorney impact

The ongoing study relies on volunteer court observers — mostly law students from SMU — who track how long it takes for courts to hear cases on an eviction docket, the cause for the eviction claim, whether landlords or plaintiffs show up or have attorneys, whether a judge confirmed the landlord properly served the tenant with a notice to vacate, and the outcome of the case.

They observed nearly 1,300 eviction hearings across five of Dallas County’s ten justice of the peace courts from November 2022 to April 2023, representing about 10% of all initial eviction cases heard in those courts.

The study found the majority of cases observed, 59%, were for nonpayment of rent. In more than a third of the cases, the reason for eviction was not clear to the observer.

Perhaps the most jarring finding was that tenants frequently do not have a lawyer to help them in court, even though tenants with legal representation are far more likely to win, the CPAL study found. Renters who had lawyers lost their cases just 7% of the time, whereas renters without lawyers lost their case — and, typically, their home — nearly 70% of the time.

Despite this, only 1 in 4 tenants had a lawyer present. About 3 in 4 landlords had a lawyer to represent them.

Farwah Raza, who leads the home preservation project of the Legal Aid of Northwest Texas, said tenants often come to court ready to make arguments that seem reasonable — that they just need a few more days to make rent, for example, or that they withheld rent because their landlord hasn’t made required repairs — but that aren’t legal grounds to keep from losing their homes.

“Some of the legal defenses to evictions are not intuitive, so folks that go in to defend themselves will arm themselves with a whole host of facts that they think will be relevant, logically. But legally, they're just not. And attorneys can sift through that [information] and we can figure out, okay, this is relevant, this is not,” Raza said.

Attorneys can also help tenants negotiate with their landlord to avoid eviction, keep an eviction judgment off their record or get renters connected to financial assistance or other supports, the study notes.

Courts without records

Unlike in criminal courts, defendants aren’t guaranteed legal representation in civil cases.

Mary Spector, who leads the civil and consumer legal clinic at the Southern Methodist University’s Dedman School of Law, said justice of the peace courts function differently than other courts. Many justices of the peace are not lawyers. The courts don’t record evidence or keep a written transcript of the proceedings, which has also made them difficult to study.

“Justices of the peace typically have had a great deal of autonomy over their courts,” Spector said.

The idea behind these courts is to provide a venue for small claims where people can represent themselves without having to get a lawyer, she said.

In eviction cases, CPAL’s data undermines that basic concept, Melton said. He said it shouldn’t be up to tenants – the defendants – to know the law enough to prove a landlord has or hasn’t followed the law in trying to take their home.

“Justice in a court designed not to need lawyers shouldn’t require a lawyer,” Melton said. “But it does.”

Landlords, as the plaintiffs bringing the eviction claim, are ostensibly responsible for making the case that they have the legal right to evict and have followed the law. But most of the time landlords aren’t required to prove they’ve met even the first procedural step in the law, the study found.

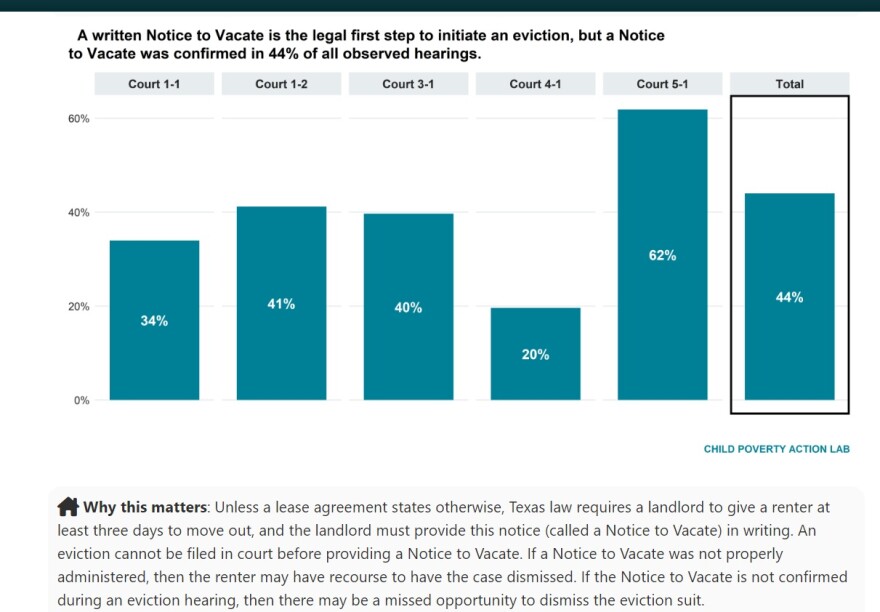

The first step in the formal eviction process is a notice to vacate, which a landlord must give to a renter in writing. In just 44% of the cases observed, landlords were required to establish that they’d followed this step.

“It’s judge-specific, it varies from judge to judge,” Raza said. “There isn’t a universal set of questions that the judges will ask.”

Swartz said this was one finding he questioned. He asks every landlord in his court if they properly served a notice to vacate, he said, but the CPAL study found his court only confirmed the notice to vacate 40% of the time. However, he was sworn in as the court’s judge part of the way through the study period and said he and his predecessor — former Judge Al Cercone — approached these cases very differently.

Swartz said justices of the peace, unlike judges in most other Texas courts, are allowed to ask questions and gather facts before ruling on a case. Unlike Cercone, who mostly relied on the tenant to raise legal defenses or challenge whether a landlord properly followed the property code when pursuing an eviction, Swartz said he asks landlords to prove they have a legal right to evict and tries to find alternatives where possible.

“I’m looking for ways to figure out both interests where [landlords] do end up with money in their pocket and the tenant does keep a roof over their head. Sometimes that means I’ll reset a case, sometimes that means I’ll abate a case, and sometimes it means I need to grant the eviction but tell folks, ‘Hey, listen, if you can work this out with the landlord, they’ll erase the judgment and vacate it like it never existed,’” Swartz said.

Another determinative factor in these cases was showing up, the study found. In 86% of cases, landlords or their representatives were present, while only 40% of tenants facing eviction came to court. When tenants don’t show up, a judge is far more likely to order their eviction.

“Tenant appearance matters heavily because when tenants do not appear, most judges will tend to by default rule in favor of the landlord automatically, without taking into consideration the facts of the case,” Harris said.

She said tenants may be unable to get out of work or find childcare, may struggle with transportation to the court or not understand the importance of coming to court. Spector said many tenants leave once they receive a notice to vacate, not realizing that document is just the beginning of the eviction process.

Low tenant appearance rates are part of the reason that the average time spent on each case — roughly four minutes — was so low, said Swartz. While Melton questioned whether justice can be adequately rendered in four minutes, Swartz said he believes that four-minute average doesn’t necessarily signal a problem.

On a typical day that he hears eviction cases, Swartz said his docket includes between 40 and 60 cases. That means some tenants and landlords will have to wait close to four hours for their case to be heard.

And when many tenants don’t show up, a lot of cases result in a default judgment, and he said he quickly check that the landlord has followed the property code before ruling and moving on.

“I'll make sure that I flip through the defaults and confirm that the notice to vacate is there, and ask if it was served properly, and then ask if everything was served that was supposed to be served. But that entire process just doesn't take very long,” he said. “So when we're talking about averages, sure, some of these cases take 15 to 20 seconds and some of these cases take ten 15 minutes.”

Long-term consequences

Evictions have been on the rise since pandemic renter protections were lifted. During the six-month study period, more than 18,000 eviction cases were filed in Dallas County, roughly 109 per day. In 57% of the observed cases, the judge ruled in favor of the landlord, giving them permission to force the tenant out of their renter home, the study found.

Young children make up the largest group of people facing eviction, according to a major national study, as mothers with kids at home lose eviction cases at higher rates. That national study also found that Black Americans are the defendants in over half of all eviction filings nationally, despite making up less than 19% of all renters.

People who’ve been evicted face higher rates of homelessness and residential instability, partly because evictions show up on background checks when they apply for apartments and jobs, advocates say.

“It’s unfortunately a lasting record that just kind of sticks around and stigmatizes people and takes away their ability to be able to find alternative housing,” Raza said.

Evictions often result in school disruptions for children, lost jobs or missed work hours, and even lost access to healthcare. People who’ve been evicted are more likely to end up in an emergency room than those who’ve never been evicted. And because rent and court fees often go to collections, their credit scores may also suffer.

“I always tell people that, while it’s probably true that poverty has some impact resulting in eviction, the reality is that eviction has a much bigger impact on creating poverty,” Melton said.

Comparing studies

The Child Poverty Action Lab has played a critical role in increasing transparency into evictions in Dallas County. In 2021, the group worked with Dallas County to begin eviction case filings in the county’s justice of the peace courts in 2021. Mary Spector, from the SMU law school, said just making basic information about eviction cases public was a “game changer.”

“While they keep records, those records were not available to the public,” Spector said.

Comparing the latest data from the court observation study to an earlier report, which was done in the summer of 2022, Harris notes that tenants were more likely to have lawyers. The share of tenants with legal representation jumped from 10% to 25%, largely the result of expanded staffing from the Dallas Eviction Advocacy Center and Legal Aid of Northwest Texas, she said.

Judges also confirmed that a notice to vacate was given more frequently – 45% of the time, compared to 33% of the time previously. And landlords won the right to evict their tenants less often in the more recent study: 72% of cases ended with a judge ruling for the landlord in the summer study, compared to 58% of the time in the spring study.

“The increased saturation of the legal aid presence in the courts, whether that is through the Dallas Eviction Advocacy Center or Legal Aid of Northwest Texas, has definitely impacted the justice of the peace courts,” Harris said.

Swartz, the judge, also thought more tenant attorneys was a good thing, because it often streamlines the hearings and is another check to make sure the process is fair.

"I'm always in favor of increasing access to justice," he said.

Swartz suggested that getting more information could help him improve his courtroom. For example, he said, there’s no feedback from higher courts to let justices of the peace know how often the evictions they authorize are overturned on appeal. That data, he said, could help justices of the peace understand blind spots where they are getting things wrong.

Spector suggests the observation project itself may be impacting the way courts operate, as well.

“I think, just being there, the courts know that people care and their job isn't just to get these [cases] through on an assembly line,” she said. “The judges may be taking a little bit more care than they were prior to this,” Spector said.

Both KERA News and the Child Poverty Action Lab are part of the Dallas Media Collaborative, a solutions journalism project focused on housing affordability in Dallas.

Got a tip? Christopher Connelly is KERA's One Crisis Away Reporter, exploring life on the financial edge. Email Christopher at cconnelly@kera.org. You can follow Christopher on Twitter @hithisischris.

KERA News is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.