At a town hall in the Southside Community Center in Fort Worth, U.S. Rep. Marc Veasey, D-Fort Worth, slammed the redistricting plan that would cut his district out of his hometown.

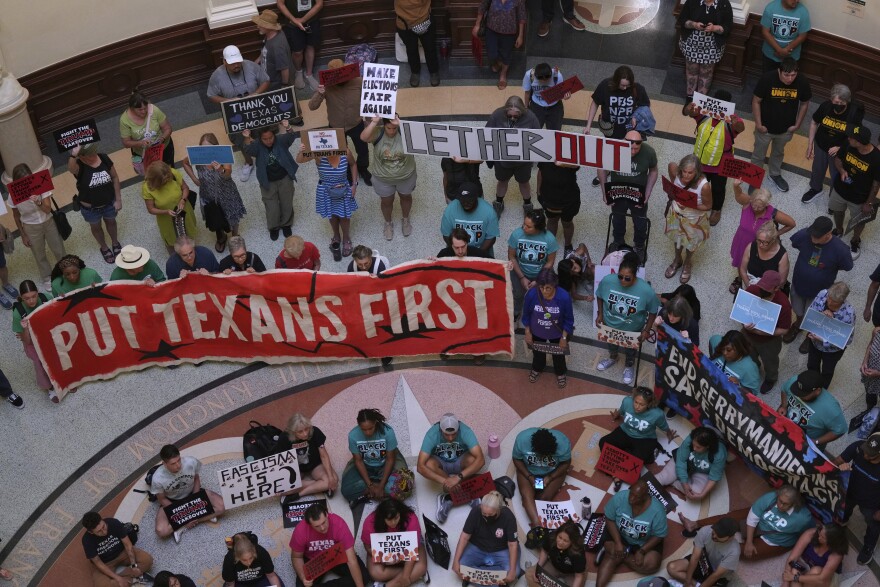

About 50 people gathered in the meeting room on Aug. 14 to hear from the Democratic congressman. Redistricting usually happens after the Census every 10 years, Veasey said.

"That was the tradition that was followed forever,” he said. “Now, it's like, ‘Hey, if it looks like we're going to have a tough year, we need to do some redistricting.’ And that is not how a functioning republic works."

At the urging of President Donald Trump, Texas Republicans redrew the state's Congressional maps to help pick up five new seats in next year’s midterm elections. That has kicked off a gerrymandering war, with California planning its own redistricting.

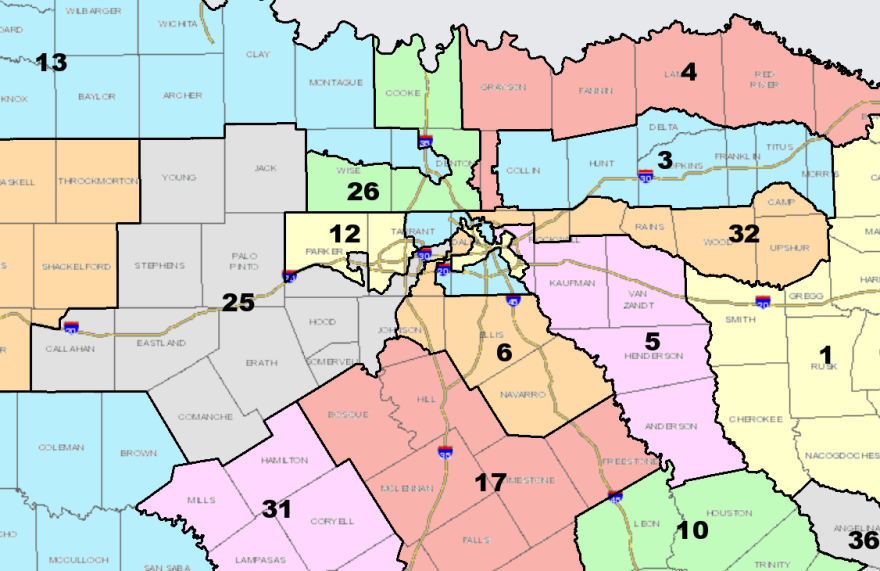

Under the new maps, Veasey's 33rd Congressional District will be confined to Dallas County. Tarrant County will largely be split between Republican districts that stretch out into rural areas.

Republicans have defended redistricting as a legal effort to gain a partisan advantage. Veasey doesn’t believe that, because the people being shuffled around are people of color, he said. CD 33, pre-redistricting, is majority Black and Hispanic, according to Census data.

“You can’t just say, ‘Oh, no, it’s okay to discriminate against Black people, because most Black people happen to be Democrats,’” Veasey told KERA News after the town hall. “That's crazy that we would start making excuses like that for people to start discriminating against people. What are we going to start making excuses for next?"

The question of racial discrimination will be worked out in court. There are already lawsuits filed over the new Congressional maps. That’s on top of three other racial gerrymandering lawsuits pending over past redistricting efforts in Tarrant County, which experts see as a “mini battleground state.”

Better representation or a return to Jim Crow?

Republicans say the new map is legal, with purely partisan goals. State Rep. Carl Tepper, R-Lubbock, told PBS the new map will benefit a wide swath of Texans.

“We're not going to try to fool you. We're not going to lie to you. These are partisan maps,” he said.

To Fort Worth resident Wallace Bridges, the new maps have the same impact as Jim Crow poll taxes or literacy tests, designed to stop Black people from voting.

“I think at the end of the day, the intent is the same,” he told KERA News, before the passage of the maps.

Bridges is an advocate for Historic Southside, a neighborhood in the largely Black and Hispanic 76104 zip code represented by Veasey in the old map. Bridges didn’t grow up there, but he decided to move there for a reason, he said.

“I had met so many professionals — Black professionals — who could have left out the neighborhood a hundred times over,” Bridges said. “But yet they chose to stay because they really believed in the community. And at that time, it was a little rougher.”

Veasey held his town hall in the Historic Southside. The congressman has always been responsive to the neighborhood’s needs, and losing him would be “a slap in the face to the people in the community,” Bridges said.

Chaplain Rich Stoglin welcomes redistricting. He was one of the only people who spoke in favor of the process at a raucous public hearing in Arlington, where the audience tried to shout him down.

“When you start looking at redistricting as a whole, it’s to help this state become better," Stoglin told KERA News.

Stoglin is the president of the Frederick Douglass Republicans of Tarrant County, which exists to make sure there are “viable candidates who happen to be people of color, and who are Republicans.”

Mainstream media presumes the Republican Party is racist and all Republicans are white, but that’s not true, Stoglin said.

Most Republicans and Republican-leaning voters are white, but the party has diversified in recent years, according to the Pew Research Center. The GOP’s success in the overwhelmingly Hispanic Rio Grande Valley in 2024 made national headlines.

"To me, the Republican Party brings hope, progress, and forward-leaning for this state to improve itself even more,” Stoglin said. “No party is going to be electing the Pope here. No party is perfect, but when you look at track records between the Democrat and the Republican Party, the Republican Party wins hands down."

Tarrant County’s shifting lines

While Texas' other major urban centers are bright blue, Tarrant County is complicated.

Republicans dominate county positions, but Joe Biden won Tarrant County in 2020 — the first Democratic presidential candidate to do so since Lyndon B. Johnson. Tarrant voters picked Donald Trump in 2024, but they also narrowly chose Democrat Colin Allred for U.S. Senate.

County GOP leaders have promised to make Tarrant County more conservative, and previous controversial redistricting efforts have given Republicans the advantage.

In 2021, state legislators redrew Texas Senate District 10, splitting up the district's diverse population and stretching its boundaries into rural areas, almost all the way to Abilene, The Texas Tribune reported.

Two racial discrimination lawsuits are pending over the Tarrant County Commissioners Court’s recent redistricting process. The court’s Republican majority voted to redraw their own precinct maps earlier this year to make Democratic Commissioner Alisa Simmons’ Precinct 2 more conservative.

The lawsuits allege that Republicans created a new conservative-leaning commissioners court seat by packing people of color into one precinct, diluting their power in others. The county has defended itself in court filings, saying the effort was 100% partisan and there’s no evidence of racial discrimination.

Federal judges in El Paso are also reviewing a racial gerrymandering case involving SD10, accusing legislators of discriminating against minority voters.

Tarrant County Justice of the Peace Precinct 5, Sergio De Leon, has spoken against these redistricting efforts. He sees them, in part, as a backlash to the county’s growing diversity, he told KERA News.

"They’re drowning us out, really, rural versus urban, so that there is more rural than there is urban, so our votes won't matter in the next election cycle," he said.

Racially discriminatory gerrymandering is illegal. Discrimination can look like “packing” voters of color into one precinct, or “cracking” their communities across districts, according to experts.

Proving racial discrimination is not easy, because voting is racially polarized, Northwestern University law professor and voting rights expert Michael Kang said. For example, most Black voters choose Democrats, and white voters tend to choose Republicans, he said.

“Places like Texas are saying, 'No, what we're really doing is we’re partisan gerrymandering. This is not racial,’” Kang said. “Because they know that if it's characterized as a partisan gerrymander, as opposed to racial gerrymander, they can get away with it.”

People who attended Veasey’s Southside town hall didn't see the benefit in redistricting.

Tellamecus Forsythe of Arlington said she went to learn how she can fight the redistricting efforts. When asked whether she thinks redistricting is a racist move, she said she couldn’t be 100% sure — but she does think it’s wrong.

“There's nothing that I've heard that makes sense for them to do this now, other than for the whim of someone else," she said.

KERA’s Caroline Love contributed to this story.

Got a tip? Email Miranda Suarez at msuarez@kera.org.

KERA News is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.