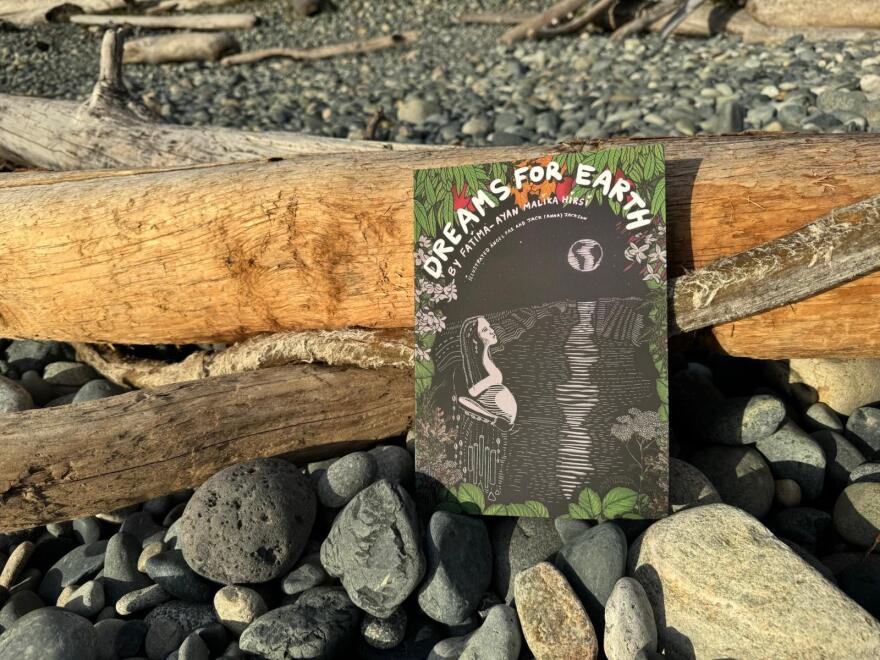

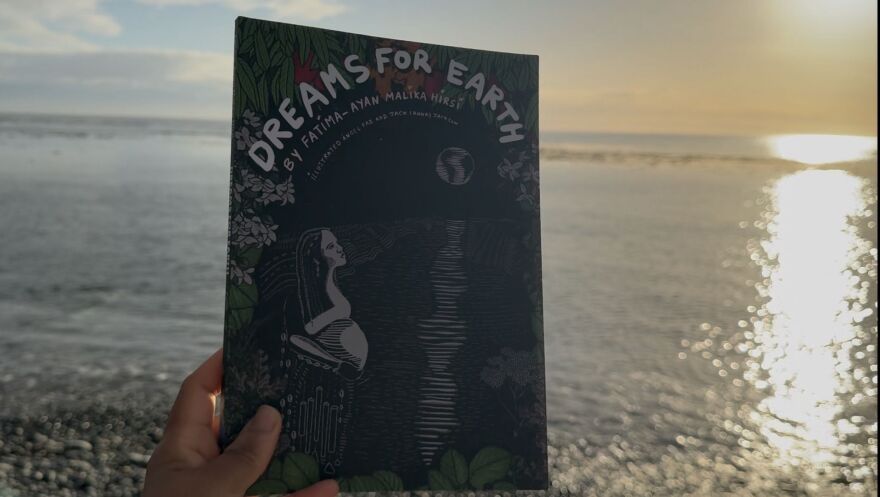

Fatima-Ayan Malika Hirsi, 37, has built a career out of turning systematic struggles into words of art. The Dallas-raised poet's debut full-length collection, Dream for Earth, was released this month by Dallas independent publisher Deep Vellum. The book gathers five years of poems written across Dallas, Oregon and Canada tackling themes of motherhood, climate grief and resilience.

Hirsi is the author of chapbooks Moon Woman and Everything Good is Dying. Her work has been featured in journals such as Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora.

“I've just always loved telling stories,” she said. “Right now that manifests as poetry. And most of my life, it's manifested as poetry.”

Hirsi spoke with us about the politics running through her work, community, and what it means to be a Black mother.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’ve always found the process of putting together a poem fascinating, can you break down your process for me? Where do you start? How do you build a line and then what comes after?

I usually sit down to a page with one of two entry points. So one is I have a line or an idea in my head, and I don't exactly know where it will go. It's like I set out on a road, and I could end up in who knows where. I am surprised at the end.

The other thing that happens is I don't have an entry point. I just sit down – need some creative time, and I just see what comes. Both of them allow for a lot of spontaneity.

I want to talk about the theme of motherhood in the book. What about your personal experience influenced how you approached this topic?

I think my experience as a Black woman who grew up in the South is really strong in my identity as a mother. So this idea that we have a responsibility to show our children not just what they are taught in schools, not just sanctioned knowledge, but the actual way that the world works, that we are forced to experience.

That’s interesting, can you describe a personal experience you have had as a Black mother that comes to mind when you think about your experience with motherhood? How does it feel different to you?

Yeah, I can think of when I was in elementary school and we were forced in – at least Florida classrooms and Texas classrooms where I grew up, we were forced to recite the Pledge of Allegiance every day and I just knew without my mom exactly telling me, but because of the way that she raised me, I knew that the words in the Pledge of Allegiance did not speak to my feelings or my experience even at that young age. So one day, I just refused to stand up and the teacher called me to the front of the classroom and asked me some questions and was not happy.

My mom had to go down to the school and she came to an arrangement with the teacher where I had to stand up, but I did not have to place my hand over my heart or recite the words. And so just that advocating for me to reflect my own opinions and my own thoughts really influences how I raise my child right now.

You grew up in Dallas, what did your community look like when you lived here? Can you give an example of one of the community building projects you are most proud of?

When I lived in Dallas, my community looked like a lot of people who cared about art, and a lot of people who did see the magic in collective kinship. So, in a lot of the art spaces that I moved in, it wasn't just about the aesthetics of art, but how can we use art to uplift others and shine a light on other experiences that maybe aren't being covered in mainstream media?

Working with Angel Faz, who is one of the collaborators on my book art, to do different projects, Decolonize Dallas, Southern Sector Rising, which was an organization that fought against environmental racism in South Dallas.

My family lived in Joppa. Joppa is directly beside a cement plant that is still running. And my mom stopped gardening because her garden was just covered in ash. She couldn't eat the vegetables she was growing. You walk outside and you just can't breathe the air. It's holding your breath till you get to the car. So my existence is in these experiences that kind of demand you not close your eyes to the things that aren't pretty.

You mentioned that the political climate in the U.S. and abroad has influenced the themes in the collection. How so?

It feels like there is just this rising tide of authoritarianism and fascism, not just in the United States, but across the world. And so as someone who cares about collective kinship, I can't help but to be influenced by all the things that I see. I want to dream of different futures for us despite the fact that this stuff is going on.

How do you incorporate politics into your arts organizing?

Thankfully the Dallas art scene has blossomed in so many new ways since I was there and starting out. But at the time I really craved a place that felt like it wasn't just a reading series where people read poems. I wanted another layer. And so I formed Dark Moon Poetry and Arts and it was a space to uplift feminine and nonbinary energies and particularly those of color. It had, like, a magical kind of witchy vibe, I guess. And there were spaces in Dallas where you could look at the the lineup of these poetry series and it just like all looked the same every time, very homogeneous, and I did not see myself reflected in that so I wanted to make a space where that wasn't the case.

Do you have any poems that are your favorite out of the book?

One that feels like it is very tied to me is “Solidarity,” and it's just a poem about collective kinship and loving everyone.

I enjoyed that poem, especially the line that says “we are roots of trees talking beneath soil.” It made me think of an unbreakable bond. Is there a specific memory that comes to mind when you read that poem?

I don't know if memory is the right word, but I certainly think of the scenes I keep seeing on my social media of people rising up against the genocide in cities across the world and just the massive swarms of people and how that's reflective of collective kinship and us being strong together despite the storms of the politicians who just don't to hear us.

What do you hope that readers take away from reading Dreams for Earth?

I hope that it inspires them to, one, feel and to move beyond feeling into action. So the point is not just to be sad but to do something about it in any way that you can.

You can be a healer, a disruptor, a storyteller. There's so many ways and there's so many ways that are interlinked, right? Like, a poem can be healing and it can be disruptive and it could inspire new visions. And so I just really hope that people find their place in this moment to do something for others.

Arts Access is an arts journalism collaboration powered by The Dallas Morning News and KERA.

This community-funded journalism initiative is funded by the Better Together Fund, Carol & Don Glendenning, City of Dallas OAC, The University of Texas at Dallas, Communities Foundation of Texas, The Dallas Foundation, Eugene McDermott Foundation, James & Gayle Halperin Foundation, Jennifer & Peter Altabef and The Meadows Foundation. The News and KERA retain full editorial control of Arts Access’ journalism.