FORT WORTH — True to the spirit of Amon Carter — who liked to proclaim Fort Worth as the city “where the West begins” — side-by-side exhibitions at his namesake museum explore the American West from two complementary angles.

The first, “Richard Avedon at the Carter,” observes the 40th anniversary of an event that put the museum on the map nationally: the 1985 opening of “In the American West,” a set of portraits by celebrated New York fashion photographer Richard Avedon.

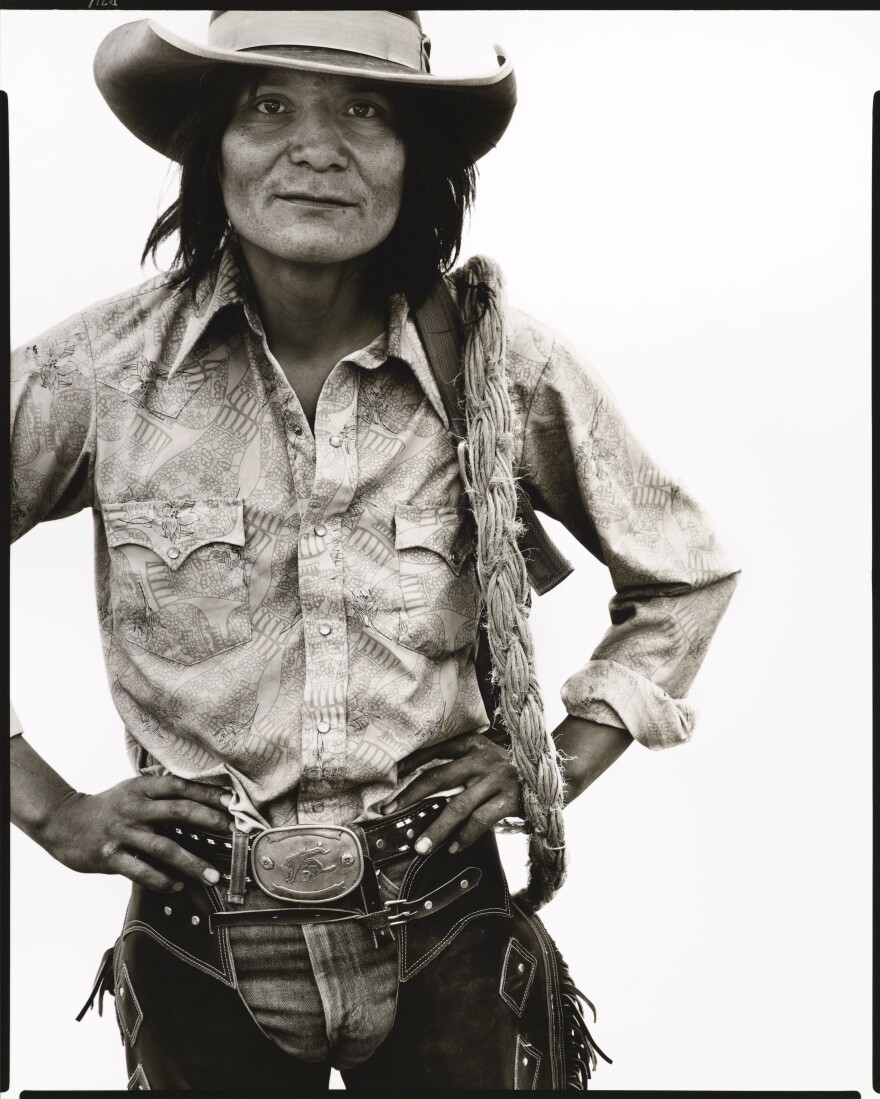

The unflinching, level gazes of Avedon’s mostly working-class subjects (oilfield workers, miners, ranchers, waitresses), and the contrast between their well-worn workday attire and Avedon’s bright white backgrounds, positioned the series in contrast to more romantic representations of the West (which are easy to find elsewhere in the Carter’s permanent collection). One of the early pictures shows Boyd Fortin, a teenager at the rattlesnake roundup in Sweetwater, Texas, holding up a dead snake; another shows Red Owens of Velma, Okla., covered in oil from his job.

Reaction was mixed, ranging from “haunting and magnificently moving” (Texas Monthly) and “gigantic and generous” (The Sunday Times) to “without any real admiration or respect” (The Atlantic). While acknowledging the monumental scope of Avedon’s effort, some found his vision cold and lacking in empathy. Among the documentation on display is a letter from the museum’s public relations coordinator, defending the exhibition against a visitor who had written an angry letter of complaint.

That vein of criticism is somewhat dispelled by the archival photographs by Laura Wilson, who accompanied Avedon on the project and documented its progress, showing friendly, informal interactions among Avedon, his team and his subjects.

Looking at the show 40 years later, I sensed that the broader American context had maybe changed more than the show’s subject in the intervening years. While Americans in difficult physical jobs work as hard as ever, Avedon’s view no longer appears as a challenge to a broadly cheerful, upbeat story of America, but instead as one in tune with a darker view of the country shared by many members of the public.

Avedon’s vision was epic in scale: After being commissioned by the Carter in 1979, he worked on the project for five summers (1979 to 1984), visited 189 towns in 17 states, made 752 portrait sittings and exposed 17,000 sheets of film, ultimately choosing 124 portraits for the series. The show drew national attention, with magazine, TV and newspaper reporters descending on Fort Worth.

Across the hall from Avedon, a different collection of mostly California-based artists is on view in “East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art,” 48 works in diverse media from the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, which introduces viewers to a wide range of artists who are probably unfamiliar to most. While a handful of those in the show, such as painters Bernice Bing, Roger Shimomura and Chiura Obata and ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu, have achieved wider recognition, most are more obscure.

The show spans a period from the earliest Chinese immigration, around the time of the 1849 gold rush, until the present day, when about 18% of Californians are Asian American. Despite the racial discrimination that peaked during the years between 1882, when the Chinese Exclusion Act forbade Chinese immigration to the U.S., and 1942, when President Franklin Roosevelt ordered Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II, the artworks here represent thriving, successful communities.

I was especially engaged by the works that depicted how a community takes root and comes to define a particular place, such as the views of San Francisco’s Chinatown (the oldest such neighborhood in North America) by Jade Fon Woo and Dong Kingman. These are complemented by pictures of the spectacular California landscape, such as Tokio Ueyama’s Monterey Cove and Bing’s more abstract Blue Mountain, that promote a sense of harmony with nature.

On a darker note, depictions of the internment camps by Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto, Koho Yamamoto and others show innocent Americans imprisoned in the desert by their democratically elected government. A drawing of camp-grown radishes by Obata, who organized art schools for his fellow internees, suggests how they tried to keep up their spirits. (Years later, his son Gyo would design DFW International Airport.)

Among the most memorable works for me were Shimomura’s slick imaginary portraits, as well as Takeshi Kawashima’s Rorschach-test-like abstractions, both of which use a visual vocabulary influenced by print media to generate catchy, iconic pictures well-suited for digital reproduction.

While it was a treat to learn about the talented artists in the show, I was less convinced by its overall organizing concept. It’s billed as a “survey of Asian American art,” but I’m not persuaded that it amounts to any such thing. For a start, the 31 artists represent so many diverse schools and approaches to art that it is hard to discern any common threads that hold them all together in a coherent group, other than that they all fall under the umbrella category of “Asian American art.”

This does not solve the problem of coherence, though, because to begin with, efforts to define this category are plagued by a certain arbitrariness. (For example, the U.S. government reclassified several groups of Central Asian Americans from “white” to “Asian” in 2023, despite reservations from within the Asian American community, while the category still excludes West Asian Americans.)

Even taking the category of Asian American art for granted, the show hardly offers a representative picture; it includes nothing from Korean American, South Asian American or mainland Southeast Asian American artists. What it offers, rather, are significant samplings of work from Chinese American, Japanese American and, to a lesser extent, Filipino American artists.

At any rate, it would have been more illuminating to see any specific group of these artists shown in connection with other, non-Asian American artists with whom they shared common artistic traits, rather than in a large show with other artists who share a theoretical identity but little artistically.

In short, the exhibition falls into a common curatorial trap: starting with abstract identity categories shaped by cultural politics rather than allowing the art itself to shape the show’s direction.

Despite that, the exhibition offers a stimulating presentation of some important and evolving aspects of the culture of the American West.

Details

“Richard Avedon at the Carter” continues through Aug. 10 and “East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art” continues through Nov. 30 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth. Tuesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., and Sundays from noon to 5 p.m. Free admission. Call 817-738-1933 or visit cartermuseum.org.

Arts Access is an arts journalism collaboration powered by The Dallas Morning News and KERA.

This community-funded journalism initiative is funded by the Better Together Fund, Carol & Don Glendenning, City of Dallas OAC, The University of Texas at Dallas, Communities Foundation of Texas, The Dallas Foundation, Eugene McDermott Foundation, James & Gayle Halperin Foundation, Jennifer & Peter Altabef and The Meadows Foundation. The News and KERA retain full editorial control of Arts Access’ journalism.