Move over, turkey. Step aside, stuffing.

Green Bean Casserole, an iconic Thanksgiving dish, turns 60 years old this year, and it's as popular as ever.

Love it or loathe it, the classic Midwestern casserole has come to mean more than just a mashup of processed food sitting next to the mashed potatoes.

"Green Bean Casserole in the Midwest seems to be, in many contexts, an unintentional performance of identity, but at other times a very purposeful expression of local identity," says Lucy Long, a folklorist, Bowling Green State University research associate and director of the nonprofit Center for Food and Culture.

Long, originally from the South, moved to Ohio 30 years ago and began noticing that the dish appeared on most Thanksgiving menus — crossing ethnic, religious and socioeconomic differences. She reported her findings in a 2007 academic paper, "Green Bean Casserole and Midwestern Identity: A Regional Foodways Aesthetic and Ethos."

Green Bean Casserole is part of the Midwest's "culinary universe," Long wrote, reflecting industrial agriculture, the bland food of our European ancestors and a fear of Mother Nature.

"You can't romanticize nature out here," she says. "Nature is not necessarily your friend, particularly if you are a farmer. If you don't constantly keep your guard up, it can destroy everything."

I can't remember a time when my mom didn't serve Green Bean Casserole at Thanksgiving.

The recipe is simple — "open cans, mix, bake," as Long describes it. It can be found online, or on the back of products that sell like crazy at the holidays — canned cream of mushroom soup, canned green beans and yes, canned, fried onions.

I love the dish, but not everyone does. My sister, Paula Kellner, lives in Nebraska and hosts our family's Thanksgiving every year. Green Bean Casserole is always on the menu, but when I asked Paula if she liked it, she was succinct:

"Ick. No. Gross."

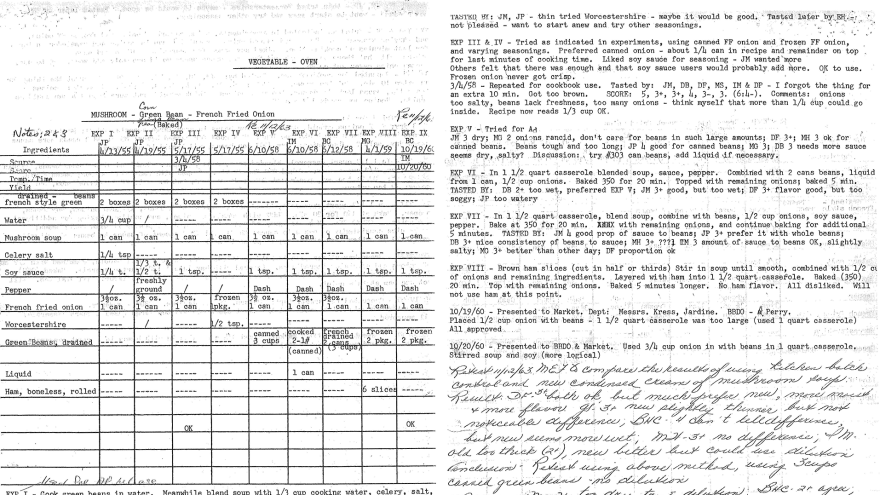

Despite its status as Midwest holiday table staple, Green Bean Casserole didn't originate in the Midwest. Dorcas Reilly, a now-retired home economist in the Campbell's Soup Co. test kitchen in New Jersey, created it in 1955 after an Associated Press reporter called, asking for a vegetable side dish, said Jane Freiman, director of the Campbell's Consumer Test Kitchens.

The original recipe shows that Reilly considered using corn, peas and even lima beans. She finally settled on "Green Bean Bake." Reilly, who still lives in New Jersey, said in a Campbell's promotional video that she created it with home cooks in mind.

"We worked in the kitchen with things that were most likely to be in most homes," she said. "It's so easy. And it's not an expensive thing to make, too."

The dish is now served in 30 million homes on Thanksgiving, and gets 70 percent of traffic on Campbell's website, Freiman says.

"It's a universally loved American tradition," she says.

Cathy Swanson, cookbook editor for Betty Crocker and Pillsbury, expects a half-million hits online this week, most looking for classic Green Bean Casserole.

"I think we have 30 versions of the Green Bean Casserole," Swanson said. "We have ones that use frozen green beans, or fresh green beans. We have recipes that are done in the slow cooker. We have a cheesy version and a gluten-free version."

I even found a recipe for a paleo version. Most of the dozen people I asked about Green Bean Casserole laughed at the dish's enduring popularity. And some said their foodie families would never stand for such processed food on their plate.

Much like Paula, my other sister, Ann Mausbach, also hates Green Bean Casserole and prefers to roast fresh green beans. Yet Ann says she still loves the idea of that communal casserole.

"It reminds you of home," Ann said. "I would associate it with Mom and, well, my family. I don't make it myself." So when she sees a casserole on the table, she says, "it's a good sign — like, 'Oh, I'm going to be with people I love.' "

As for my investigation, the dish came out much like the recipe said it would, "hot and bubbly." It was also creamy and comforting and a little crunchy.

So take that, roasted root vegetables and cranberry chutney and all you other sophisticated side dishes. At 60 years old and counting, Green Bean Casserole is here to stay.

Peggy Lowe is a reporter for Harvest Public Media, a public radio reporting collaboration that focuses on agriculture and food production.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.