Local governments are days away from having to comply with a state law that cuts off their ability to regulate a huge swath of issues. That new law – which is slated to go into effect Friday – may well set off years of lawsuits and regulatory confusion.

That is, assuming the law goes into effect as planned. Some of Texas’ largest cities have sued to block it.

If enforced, HB 2127 would have massive implications for cities and counties across Texas, and for the people who live in them. It potentially neuters countless local policies and ordinances governing nearly every aspect of life and governance and would significantly restrict local government’s ability to act on issues of concern to residents.

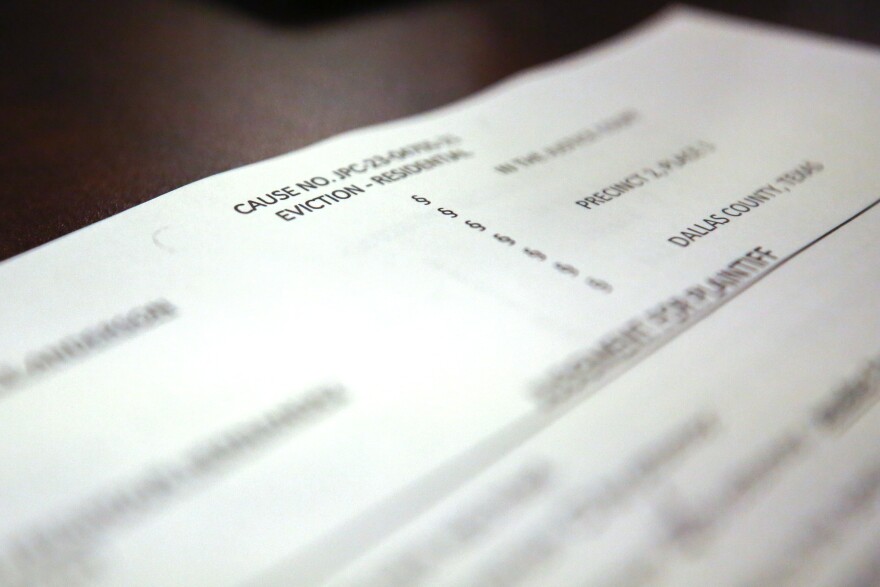

One example of this swirling confusion are rules in Dallas and Austin that that gives renters extra time to pay rent before a landlord can evict them. The ordinances ensure what some call a right for renters to “cure” the late rent before losing their home.

House Bill 2127, when it becomes law, blocks local governments from adopting, enforcing or maintaining any “ordinance, order, or rule regulating conduct….regulating evictions or otherwise prohibiting, restricting, or delaying” the eviction process.

“HB 2127 is pretty clear and straightforward: Local governments cannot adopt opportunity to cure or right to cure ordinances at the local level. However, that clarity is misleading because it’s embedded in a whole lot of lack of clarity around the bill,” said Ben Martin from the tenant rights group Texas Housers.

So Dallas is “considering its options,” a city official told KERA recently. Austin’s right-to-cure rules “remain legal requirements for landlords,” a spokesperson said. Neither appear poised to

But the bill goes much, much further than renter issues.

Death Star or regulatory clarity?

The measure preempts local governments from making rules that go beyond what state lawmakers have allowed in areas of the law that include agriculture, business and commerce, finance, insurance, labor, occupations and property codes.

“Unless expressly authorized by another statute, a municipality or county may not adopt, enforce or maintain an ordinance, order, or rule regulating conduct in a field of regulation that is occupied by a provision of this code,” the soon-to-be-law reads.

In only a handful of areas does it get as granular as the provisions barring local governments from intervening in the eviction process.

HB 2127 also strips governments of immunity from lawsuits for any local rules, policies, laws or practices that run afoul, and empowers pretty much anyone to sue a city or county.

That’s despite the bill’s name: The Texas Regulatory Consistency Act. Republican lawmakers and Gov. Greg Abbott supported the bill because it would create clarity for businesses. The bill drew strong support from industry lobbyists in Austin.

“Texas won’t allow ill-conceived & inconsistent decisions to take down the ship that drives our state’s economy,” Burrows tweeted last spring as the bill neared the finish line.

Critics dubbed it the “Death Star” bill that'll obliterate local authority to act on local problems, undermining the power of voters to determine how their communities are shaped. The law would essentially require cities to lobby state lawmakers, who meet every other year, to pass a law allowing them to take actions that, currently, city councils can enact on their own.

A legal battle

Despite its soon-to-become-law status, HB 2127 remains shrouded in question marks as cities sue to block its implementation.

The City of Houston filed suit against the state to block it. They argue that it is so broad and so vague as to violate the state constitution.

At stake are countless city and county rules, ordinances, policies and practices, potentially including some humdrum policies that have been on the books for ages. That could include rules limiting fireworks, governing city and county contracts, water conservation and air quality efforts, payday lending limits, and more.

A Plano official told KERA in May he wasn’t sure if the city could block people from piling farm animals onto suburban yards. It’s one of many local code compliance rules that may run afoul of HB 2127.

“If my neighbor decides that they want to have roosters and an unlimited amount of chickens, or they want to have pigs in their front and back yard, we have real questions now,” said Plano government relations director Andrew Fortune. “Is that within our purview for us to regulate, and make sure that in a residential neighborhood you’re not being woken up at the crack of dawn by a rooster?”

Since then, Plano became one of many cities across the state joining Houston’s lawsuit, including El Paso, San Antonio, Denton, and Arlington. Austin and Dallas have not joined the lawsuit, though individual city council members have.

A hearing in the case is scheduled for Wednesday.

For now, Ben Martin from Texas Housers said he’s pleased to see cities pushing back. He hasn’t seen much evidence of cities repealing ordinances that may run afoul of HB 2127 in anticipation of it going into effect.

“I’ve been heartened that cities have shown some bravery in protecting their residents in response to this bill. I hope that they will continue to do so until it’s very clear by law that they’re able to do that,” he said.

A ‘right to cure’

Dallas and Austin are the only two cities that have local eviction rules giving extra time for tenants to pay rent and late fees before their landlord can begin the eviction process. These “right-to-cure” provisions are the norm in a majority of states, according to Martin.

The rules offer what is essentially an extended grace period for a tenant who is late on rent. If they pay the rent and late fees by the end of the grace period, they can’t be evicted. If they don’t, a landlord can proceed with the eviction as normal.

Landlord associations have argued that the measures only kick the can down the road, because many poor tenants simply can’t afford the rent, even if they have another week to pay it. Jason Simon from the Apartment Association of Greater Dallas argued that a permanent rental assistance fund is a better way to serve tenants being evicted because they simply facing a cash crunch.

“Dallas is a renter-majority city. Use your general fund dollars and stand up a permanent rental assistance fund,” Simon said.

Martin also wants to see permanent rental assistance funds. While he concedes right-to-cure measures may only delay the inevitable for some, he argues they’re still important. But for others who can’t pay rent on the first of the month because of a short-term setback like an emergency car repair, it may offer needed time to borrow money from a friend or work a few extra shifts to catch back up on rent.

Depending on how the lawsuits around HB 2127 play out, it’s not clear how long those right-to-cure rules – and countless other local policies and rules across the state – will continue to be enforceable.

Got a tip? Christopher Connelly is KERA's One Crisis Away Reporter, exploring life on the financial edge. Email Christopher at cconnelly@kera.org.You can follow Christopher on Twitter @hithisischris.

KERA News is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.