After serving two years in prison for possession of meth, Toby Savitz found herself in a series of low-paying jobs with no real path forward. She finally kicked the door open after landing a position at a nonprofit that helps ex-offenders like her. But she admits there aren’t enough jobs like hers to go around.

As part of our series One Crisis Away: The Price of Prison, Savitz tells her story about starting from scratch after incarceration and rising to program director at Pathfinders in Fort Worth — and how her journey is the exception, not the rule.

I was an addict. I was an addict for many years, and I became incarcerated as a direct result of my addiction. I was charged and convicted of possession of narcotics. I went in 2006 and came out in the summer of 2008.

As I exited prison, I had made all these new plans for my life, and I found — virtually from the moment I stepped out of the gate — that there were many, many more barriers in place than I expected there to be.

I exited with no clothing that fit, so I was dependent on a community group that donated clothing. They gave me one outfit for church, one outfit to apply for work in and one outfit that I could wear, you know, at home. So, that was basically what I started my new life with.

You're immediately looking for work. I've taken a series of low paying jobs — I'll just say it, bad jobs — to just get started, to just get me back into the community. The first job that I had was $10 an hour. This was not enough to obtain an apartment — even if somebody had been willing to rent to me.

I actually stayed with that company for a few years and rose through multiple layers of roles within that company. Through that entire time, I never made the same amount as the other people in lateral positions.

I was interested in obtaining my social work degree, and I was told that I would have to apply to the state licensing board so that they could determine whether I would be eligible for that license.

I followed all of the guidelines set forth by the state, submitted all of the documents, and the response was, "We've declined to answer at this time." Which means I will have to invest in all of my schooling and just hope that in the end it all works out and this state will be willing to license me, and that's a really expensive proposition when you don't know the answer. It's a giant gamble.

At one point I was making $16 an hour, and that was more than anybody else I knew who had a [record] and I began to wonder ... is this it? Have I hit the ceiling cap for what I can make with my type of background?

I had been sharing my story of addiction in different places, and that was how I originally came in contact with Pathfinders. I was doing some volunteer work for them, and I asked that question of them: Am I at a place where this is all I should expect? Pathfinders said, "Come in and let's talk about it."

That was really the changing point for me.

Some months later, a position became available with Pathfinders, and they called me back and said, "How about you come in for an interview?" So, I'm the director of programs, and this is my third role with Pathfinders.

I look at what I do as not just an opportunity for growth for myself, but as a way to keep the door open for people behind me.

Paying your debt to society by being incarcerated is just a simple myth. I think it would be a little more accurate if a judge said something along the lines of, "I sentence you to six years in prison as your down payment. And once you complete your down payment, that time of being incarcerated, I sentence you to a lifetime of reduced earning capacity. I sentence you to a lifetime of reduced ability to rent or own a home."

There's so many things — you can't probate a will if you have a felony, so your family member has to find somebody else to be the executor of their estate.

I mean, these financial hardships just go on and on.

» » » » »

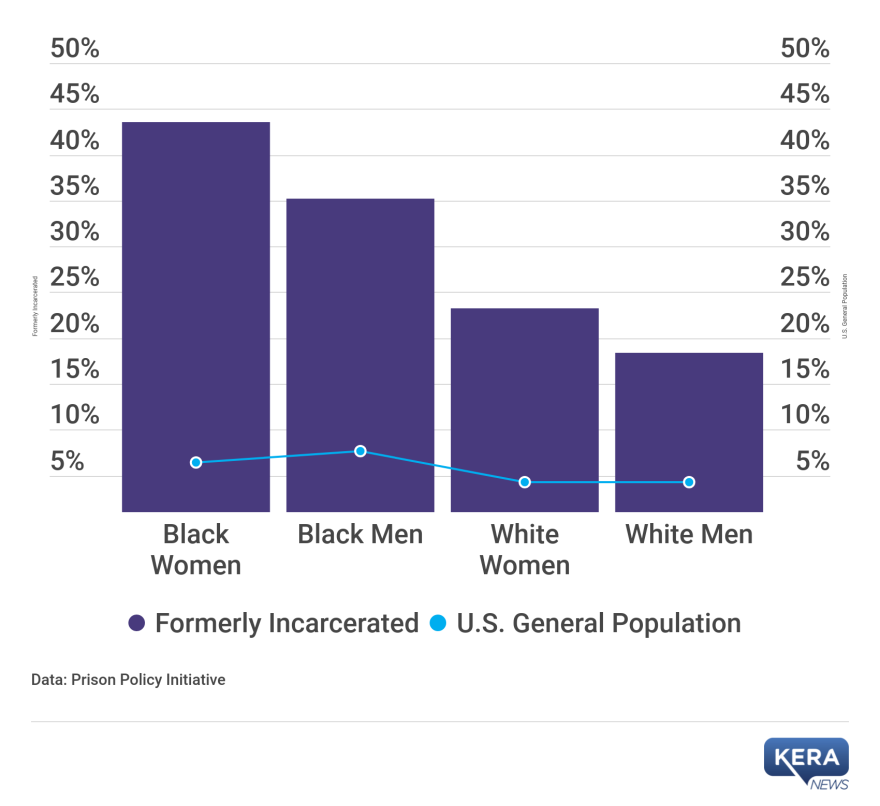

CHART: Unemployment rates for ex-offenders

Job advancement after prison is difficult. So is simply getting (and keeping) a job.

The chasm between unemployment rates for people who have a prison record (the purple bars) and the U.S. general public (light blue dots) spreads up to 39 percentage points:

Context: Peak unemployment for the general population during the Great Depression (1933) was 25%.

» Chart details:

• The disaggregated data used in the chart above is for people ages 35 to 44. Ex-offender data is for those released between 2005 and 2008, within four years of their release.

• The Prison Policy Initiative was not able to gather comparable data on Hispanic rates of unemployment by gender and age to place alongside the stats for whites and African Americans. However you can view a chart here of formerly-incarcerated and general-public Hispanic unemployment rates by gender alone.

» Coming Oct. 22: Ed Ates was convicted of murder in the '90s. He has maintained his innocence since the beginning, and hundreds of people believe him. The parole board released him after 20 years in prison, so he’s back with the family he loves. But his two decades away meant financial hardship for his wife and kids — and lost time he can never reclaim.

» About this series: One Crisis Away project's Price of Prison examines how time behind bars erodes wealth — for offenders, for families and for generations. Explore more stories in the series.