In 1998, Harris County sheriff’s deputies arrested John Geddes Lawrence Jr. and Tyron Garner for allegedly having sex.

That arrest was possible under Texas’ Homosexual Conduct Law, which criminalized gay sex. Lawrence, Garner and their lawyers challenged the law and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court.

In 2003, they won.

In Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court declared sodomy laws unconstitutional. Gay relationships were decriminalized nationwide, paving the way for later civil rights victories, like the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015.

None of that would have been possible without the decades of activism by queer Texans, UNT history professor Wesley Phelps argues in his new book, Before Lawrence v. Texas: The Making of a Queer Social Movement.

Phelps traces more than a century of challenges to sodomy laws in Texas and highlights the people who laid the legal foundation for the Lawrence v. Texas decision. Some of the fundamental members of that movement were activists in Dallas.

Phelps joined KERA to talk about his book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was life like for queer Texans under sodomy laws, particularly the Homosexual Conduct Law of 1973?

There had been sodomy laws in the past that outlawed non-procreative sexual behavior among everyone. [The Homosexual Conduct Law] was specifically targeted at gay and lesbian citizens.

The law served as a legal justification for a range of discrimination against gay and lesbian Texans, from employment and family law to the allocation of social services -- just a number of ways that gays and lesbians were discriminated against because, according to the law, they were presumed criminals.

And police actively enforced this law.

Absolutely. The Dallas Police Department, like police departments across the country, had what was known as a vice unit, and this was the unit that was responsible for sex crimes, policing, prostitution, things like that. But they also policed same-sex sexual behavior.

One of the ways they did that was by hiding out in places where particularly gay men were known to congregate and cruise and sometimes have sexual encounters, places like public restrooms. They would often hide in the walls, hide in ceilings. There was also a rash of bar raids of gay and lesbian establishments by the police department.

How did people push back against sodomy laws in Texas?

Gays and lesbians started to come together and create some organizations. The Dallas Gay Political Caucus was one of the first kind of activist gay and lesbian organizations in Dallas. There was also one in Houston, the Houston Gay Political Caucus. There were similar organizations in Austin and San Antonio and Galveston.

What they were often doing in the early and mid 1970s [was] trying to kind of push back against some of the discrimination that they were facing. A lot of that came from the sodomy law. But it took activists several years to come around to the idea that maybe we should challenge the legitimacy of the sodomy law itself.

In the 1970s, they're putting together patrol units in places like Oak Lawn in Dallas, Montrose in Houston, to patrol the police on the one hand, and also to cut down on some violence that they were experiencing. They also were filing complaints with local police departments about their treatment. They were filing complaints about discrimination in employment. And then gradually, by the late 1970s, activists in Dallas and Houston decide, we've really got to challenge the Homosexual Conduct Law itself.

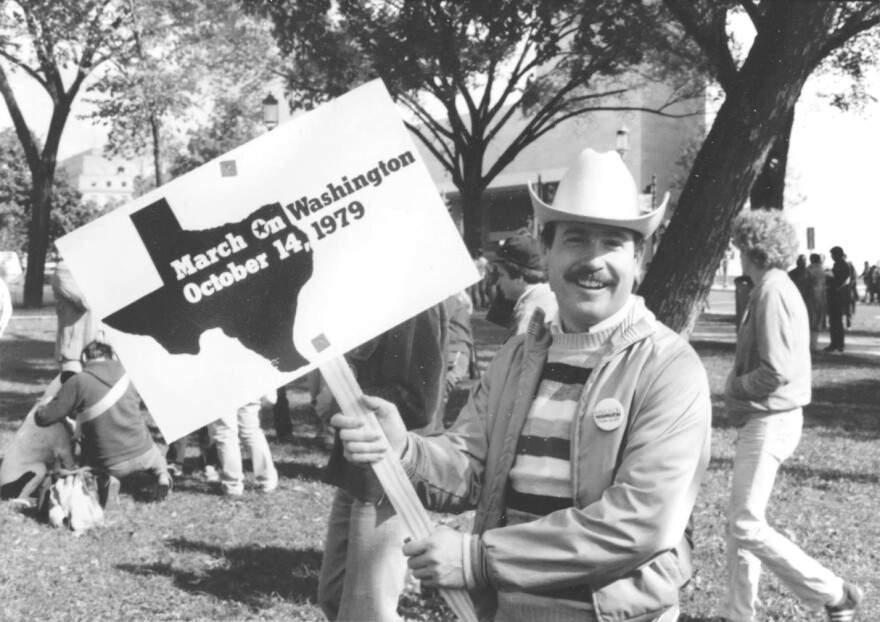

Tell us about Dallas' role in this push against the sodomy law, and the activist who’s on the cover of your book: Don Baker.

Don Baker is the reason I wanted to write this book. It was his story that I first encountered in the archives at the Briscoe Center at UT Austin.

Dallas activists were absolutely central to challenging the Texas sodomy law beginning in the late 1970s and going all the way up into the 1990s. Don Baker had grown up in Dallas. He was from Oak Cliff. He had a very long process of coming to terms with his own sexual orientation, but by his late twenties, he had come to accept that he was gay, and he moved back to Dallas and became a substitute teacher in the Dallas school district.

Things were going really well for him, until one day, the superintendent of the Dallas Independent School District announced that he didn't think there were any gay people working in the school district, and if they were, they would be fired immediately.

That really propelled [Baker] into a life of activism. In 1979, he was approached by an organization known as the Texas Human Rights Foundation, and he filed a constitutional case, a federal lawsuit against the Texas Homosexual Conduct Law. And that became Baker v. Wade.

The Wade in that case is, of course, Henry Wade, the same defendant in Roe v. Wade. So there are a lot of interesting Texas connections here.

Don Baker's case, I argue, is the most important case against the Texas Homosexual Conduct Law before Lawrence v. Texas in the 21st century. They initially won. They got a favorable ruling from a district federal court in 1982 that was then unfortunately overturned by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans in 1985. And then the Supreme Court refused to hear [the case].

It was a temporary victory, but I argue in the book it was important for this long-term fight against the Texas sodomy law. It really laid the groundwork for the eventual success in Lawrence v. Texas in 2003.

You open the book with a quote from Don Baker, talking about his legal battle: “You have to look at the long-term, not the short-term in this case.” How do you think this quote resonates with civil rights struggles for queer people today?

I think it's important to keep in mind that Don Baker said that when it was becoming clear that the favorable ruling he had gotten in his case was going to be overturned, and that the Supreme Court probably was not going to hear this case.

He wanted to explain to people that this is a long-term battle. We're going to have short-term victories. We're going to have short-term defeats. But if we keep this long-term goal in mind, we can eventually succeed. And I think that's so relevant for today when we're seeing increasing threats to queer equality.

We saw with the Dobbs decision last year, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. That, of course, was a devastating decision for women's reproductive rights. But it's also a warning sign for any constitutional protections that are based on the right to privacy. Of course, Lawrence v. Texas, the case that finally overturned the Texas sodomy law and laws like it, that ruling was based only on privacy. It wasn't based on equal protection.

I think decisions like Lawrence v. Texas are very much in jeopardy. If we don't have that decision, all of the other gains for queer equality that have come about since then are also in jeopardy. Marriage equality is unthinkable as long as the sexual relationships between gay couples were criminalized. Things like the military policy of Don't Ask, Don't Tell being repealed. That victory just seems very unlikely if gay sex is still criminalized.

I think there are real challenges ahead, and I think that's why that quote is so great, because Don Baker is saying, let's don't lose sight of our long-term battle here — and the battle may never be totally won.

Phelps is also working on a podcast called Queering the Lone Star State, which explores in detail the cases he writes about in the book. It’s scheduled for release in June, which marks Pride Month and the 20th anniversary of the Lawrence v. Texas decision.

Got a tip? Email Miranda Suarez at msuarez@kera.org. You can follow Miranda on Twitter @MirandaRSuarez.

KERA News is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.